Lessons From Climate Change Debates

As Republicans embark on a project to restructure the American economy, they could take some lessons from the previous attempt

I. A Dumb But Leading Policy

It’s been a little while since I sat down to write a blog post, but my most recent source of inspiration came from about a month ago, when Josh Hawley proposed a bill to mail Americans “tariff rebates”. The “rebates”, in practice just a $600.00 check, are incredibly bad policy as written. If one were to pass a “tariff rebate” in today’s environment, which has substantial tariff uncertainty, you’d want to peg the payout to the actual value of the money raised. That amount would probably be substantially lower than $600 per taxpayer, and probably isn’t really even knowable in advance. The bill was, in practice, just an opportunity for Hawley to pull a stunt demonstrating how “working class” the Republican Party is in 2025. The real purpose was likely groundwork for his almost-inevitable 2028 presidential run.

The bill has bounced around in my head for a while, however. The “industrial policy” that Republicans (and to some extent Democrats) are pursuing will likely transform the American economy at most levels. We don’t really know what the economy will look like after the fact - Trump’s 10% stake in Intel, for example, opens up a future whose industrial organization is very different and much worse than the present. But we do know that the economy of 10 years from now looks substantially different from the economy of today. We also can sort of percieve some basic facts.

The economy of the future will be far more energy intensive. Some of this will come from reshoring factories, which consume lots of energy (particularly in a high-automation scenario). Some of this will come from AI datacenters, which are already pushing up American power consumption and energy costs. If we’re smart, the economy of the future relies a little less on foreign trade (basic supply chain concerns) and a lot less on China (less basic IP theft and strategic bottleneck concerns). It probably also features substantially more automation of everything from Ubers to cooking to grocery stores.

The “reliance on China” part is particualrly challenging because of the way modern supply chains work. Instead of things like, “we bought this shirt from China”, modern supply chain reliance looks more like “the one $20 component crucial for the $4,000 machine to work comes from China, and when that goes down so does the entire factory line. This part cannot be made anywhere else”. If a part starts in factory A, then moves to factories B, C, and D. If factories A and B are in China, and factories C and D are in China, then only half of the value comes from China. But the exposure to Chinese supply disruptions are still 100%. Moving factory B from China moves 25% of production value to the US, but the part is still 100% reliant on China deciding not to disrupt supply. To make a long story short, there is a lot in American manufacturing that has to change.

II. Deja Vu

This sort of full-scale economic restructuring led by the state is pretty rare in American history. Fortunately for us, however, the Democrats recently embarked on a very similar looking project to decarbonize the economy. Deep decarbonization is, as it turns out, really hard. New technologies have to achieve cost parity to sustain the same level of consumption (green power, EVs). Less visible to consumers, industrial processes (steel, concrete, asphalt manufacturing) have to completely change. Democrats had to do a lot of innovation on both policy and politics to pass even a small portion of their agenda. If republicans plan to pass similarly scoped plans, they may as well take notes.

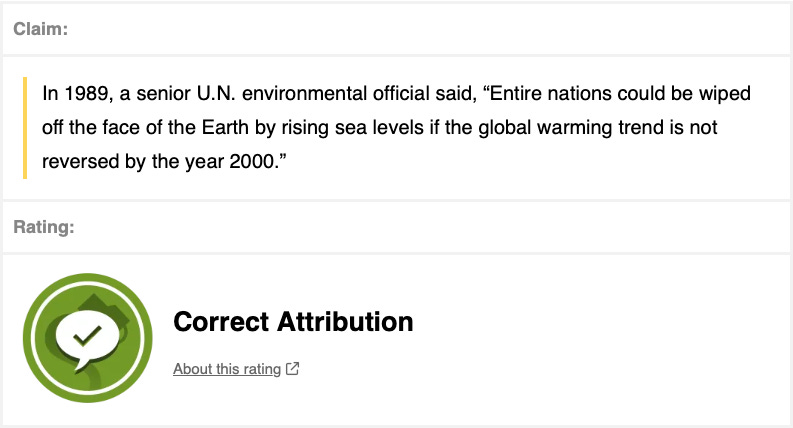

The first step of any whole-of-economy transformation is (obviously) convincing everyone that it is a good idea (in theory!) to transform the economy. On this front, climate change advocates got off to a strong start. They made some pretty catastrophic predictions about what would happen by 2020-2030 if no action was taken. Fresh off the success story of the Ozone Hole, most of the world’s respectable intelligensia listened. Elementary schoolers, already being taught that the earth was valuable and needed to be protected, recieved more climate change programming as well.

“We need to do something about climate change” was a pretty good starting point. The only question, then, was what exactly we were supposed to do. In the early 2000s, the world had not yet really invented low-emissions technologies which still enabled growth, so emissions reduction strategies centered around things like “turn off the lights in your house”, “wear a sweater instead of using a thermostat”, or “drive a Toyota Prius”. These were all extremely unpopular positions, so the transition from “do something” to “follow these recommendations” did substantial damage to the climate change cause.

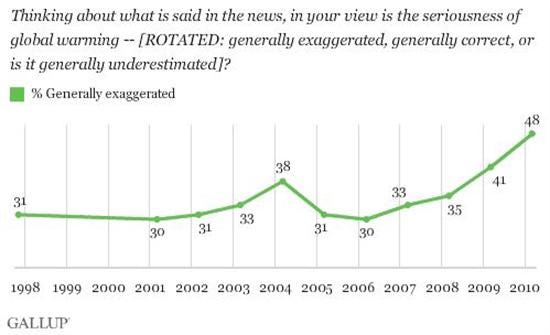

In fact, the early climate change recommendations were so politically toxic that they substantially damaged the power of the movement. People who weren’t interested in turning off their thermostat decided they preferred to ignore the problem, and rates of climate change denial (or disinterest) spiked. The Experts, having previously agreed that climate change had to be fixed, and that political consent was more important than truth telling, began to increase the hyperbole of their predictions.

It turned out that the most potent ways to fix climate change was to innovate our way out of the problem. LEDs are several times more efficient than incandescent bulbs, so your lights can stay on. In the intervening decades, we invented good electric motors and lithium-ion batteries. Instead of switching to Priuses to lower emissions, Americans got to drive Rivian R1Ts, Ford F150 Lightnings, and Tesla Model Ys. A decarbonizing grid means you get to leave your thermostat on. That’s a much more appealing political pitch. Rivians may be good for the climate, but they also hit 60 miles per hour faster than a Lamborghini - the climate change impact is almost an accident.

The problem with this strategy is that it would have sounded insane to activists in 1999. “The best way for you to lower auto emissions is to wait 12 years while we invent lithium-ion batteries and scale them up to the size of cars, then wait a few more years until we scale up production and drive down costs enough to cause a preference cascade. But for right now your best move is to sit tight and allocate a few billion dollars to research budgets.” No activist would have believed you. First, because it leaves them with no near-term deliverables. Even more importantly, however, it means that even if we invent the technology, political resistance in the future could sink the whole plan.

In fact, “political resistance in the future threatens to sink the whole plan” basically is happening right now for clean-energy power generation. We now have the technology to deploy substantial amounts of solar power at competitive prices (even when counting sufficient battery storage to distribute load). But Republicans are blocking solar and (especially) wind power deployment, seemingly because the president just has a lingering and irrational grudge against wind turbines. Among the things that Trump believes about wind turbines:

They cause cancer

They kill birds

They kill whales (?)

Climate change activists ended up achieving about half of their goals. The IRA achieved substantial emissions reductions. It created tax credits for the new technologies that would reduce carbon emissions, and created legal pathways to implement them (… kind of). It also created even more grant opportunities for the few technologies (eg, geothermal) that have not yet made it to fruition. The IRA is expected to get us 50% of the way to net zero. While some activists will pan that as “not enough”, it represents lots of progress - probably sufficient progress, after removing the hyperbole from current activist claims.

III. Notetaking

So, what did the global warming/climate change advocacy complex do right, and what mistakes did they make? What did advocates forget about, or do differently if they were to do it again?

I suspect that the first mistake climate change activists made was to start juicing numbers after their original political pitch didn’t really scare people into giving up their thermostats. The juiced claims just sounded wrong to people. When all of those “under water by 2020” and similar predictions did come due in 2020, they looked even more ridiculous, leading to a viscious cycle of less trust → more hyperbole → less trust.

Climate change activists also had a complicated relationship with technology. On the one hand, early tech subsidy programs (like tradeable EV sales credits that Tesla sells to GM, Ford, and Stellantis for selling cars that were too polluting) played an important role in deploying the technologies needed for decarbonization. On the other hand, insufficient faith in technological progress led liberals to adopt unpopular policies as backstops. One notable example of this was trying to ban incandescent light bulbs. One will recall that the idea was to replace dirty sources like coal and oil with clean sources like wind and solar. If we’re already going to do that, then what’s the problem with an inefficient lightbulb - clean electricity will power it either way!

Further on the topic of technology, I sort of understand why activists get antsy about the idea of waiting for technology to emerge. Political energy doesn’t store well over time - if you have people who are motivated to do a protest, and you tell them “come back in 10 years when the EVs are ready”, they won’t come back. Political change movements want things to do and advocate for now, but policy elites did a poor job of picking targets which preserve popularity to the median voter.

Speaking of which, climate activists also missed some critically important policy goals which were in retrospect obvious. For example, climate activists knew they would need to replace old, dirty power plants with new, renewable ones. Unfortunately, it turns out that connecting a new power plant to the grid requires an exhaustive study of what potential grid upgrades need to happen. To connect a new power source, you need to do the study, then build the upgrades, and then connect your new power plant. But upgrading existing parts of the power grid is subject to NEPA review, and will itself take several years. The end result is that it’s almost impossible to build new power plants.

The climate change activists did not realize this was a problem until after 1) passing the IRA, and 2) having clean energy developers try to take advantage of IRA tax credits and get stuck. The result is that the IRA will likely not do very much on the clean power front. A similar claim can be made about EVs - adoption is now primarily held up by a lack of fast chargers. We don’t have fast chargers because they pull a lot of energy from the grid at once, which requires similar studies to the power source connections.

It’s sort of funny to contrast these problems with what climate change activists thought was a good use of their time in the early 2010s. They tried to ban incandescent lightbulbs. They passed rooftop solar tax credits. They passed fines for auto makers if they built the cars (read: pickup trucks) people actually wanted to buy. In general, activists tended to work forwards from “things I can see in my life which are dirty”. A more effective approach would have started from “what is a politically viable clean future” and worked backwards from there to prepare our regulatory code for the deployment of those technologies.

IV. Applicable Lessons

Some lessons aren’t even unique to one side or the other here. In order to convert to clean energy, or reindustrialize America, we need to fix grid interconnection. The other lesson, however, is that every political objective has intermediate steps. Both climate change activists and reindustrializers have convinced Americans that their plans are worth doing at a high level. Both then proceeded to embark on some extremely unpopular intermediate steps - energy efficiency mandates for climate, tariffs for reindustrialization.

At a high level, America is not an industrial country for lots of reasons, but tariffs will solve none of those reasons by themselves. If they were stapled to some kind of larger agenda, they could provide more immediate incentives for a transition that is also feasible. But without that larger agenda, the tariffs are not helpful. What might that agenda look like?

IVa. Permit Timelines

One major problem is those energy connections. Inputs are a big problem (cheaper energy is always better) but American energy prices are actually quite low in global terms (yes, even compared to China). The problem is that factories in America tend to get stuck in a thicket of permits. Permits are required to connect to water systems, permits to connect to power grids, permits to do pollution, etc. It is notable that recent US manfuacturing success stories like Rivian weren’t made in new-build factories. Rivian’s factory, particularly, used to be occupied by Mitubishi, and Rivian could only afford it after it was planned for demolition.

I do understand that new companies are going to tend to prefer old factories to new ones because they are, indeed, cheaper. On the other hand, most industrial successes seem to be either “while they’re going to knock this down anyways…” or “the CEO is Elon Musk and we’re going to hack our way around every permit”. Tesla’s original factory was a tent, because building a permanent factory in California is too hard. When Elon Musk goes to build a data center, the power source is portable gas generators, because they’re available immediately and grid connections are annoying and slow.

It’s unfortunate that Elon and DOGE ended up being about USAID, because it would be nice to have someone with a visceral understanding of how slow and expensive every permit is to consult on how to remove as many permits from industrial setup as possible.

Permits for energy transmission infrastructure are also a substantial problem. No consumer really sees how long these take, but utilities struggle to build adequate transmission because of NIMBYism and environmental review. Work to fix this is under way already, especially as datacenters have spiked power costs and focused public attention. Neverthelss, exempting transmission infrastructure from environmental review (or deleting it altogether) should be high on any list of industrialization priorities.

IVb. Location Challenges

It’s also worth mentioning another thesis which I heard a few months ago on Odd Lots. Manufacturing is hard, and so optimizing final cost is usually less about input costs (raw materials, energy) and more about putting together a viable assembly process. In order to do that, you need to have smart people to work in manufacturing if a country is high income - people who debug robots, detect and fix flaws, etc. In addition to high incomes, those people demand cultural amenities - ie, they want to live in cities. But American cities have a substantial problem of NIMBYism, which prevents factories from being located there.

Getting people to live in Normal, Illinois and similarly sized towns en masse is hard, but with current NIMBY constraints in cities, it would also be necessary. If we want smart people in the US to build things, we need to be able to build things where smart people live - eg, Brooklyn. If we can’t have factories in Brooklyn, they’re much more likely to move to Shanghai (where other smart people are) than Normal (which attracts very few smart people). New Yorkers work in finance, trading and tech companies, because those things are legal activities there; but building or operating a factory is not.

“How does one do manufacturing in Brooklyn” (or more accurately, how can the federal government force NYC to allow manufacturing in Brooklyn, in a way that is politically vaiable) is not an easy question, and there are too many problems to really name. But this is the sort of laborious digging that someone needs to do if reindustrializers are going to succeed. All of these fixes will take effort and advocacy, but none of them are glamours. They will struggle to attract attention if there isn’t a coherent road map for them. Tariffs are easy and glamorous - as were carbon taxes and lightbulb bans. Mistakes happen because they’re easy, while the right way to do things is hard.

IVc. Adversariality

One other thing worth adding is that reindustrialization opponents are adversarial in a way that climate change is not. Net Zero is a pretty fixed target - it’s not like the world starts getting hotter automatically once you invent EVs. But reindustrialization opponents are indeed a moving target. If America fixes its permitting regime, China will shovel yet more money into industrial subsidies, which we will then have to counteract. If congress passes laws which penalize existing local NIMBYism, NIMBYs will invent new ways of obstructing progress.

These are, in fairness, genuinely hard problems which I don’t know the answer to. Fortunately, these are future problems, which we only have to deal with if we’re already on the right track.

> First, because it leaves them with no near-term deliverables. Even more importantly, however, it means that even if we invent the technology, political resistance in the future could sink the whole plan.

Even even more importantly, it provides no psychological benefit of struggle in the way fighting with people who are trying to have their lives not made worse does. That's an uncharitable way to say it, but I don't know how else to phrase it well. You touch on it a bit later, but I think it's important to note that in many ways you cannot have a progressive advocacy movement that is long-thinking and rational in the ways required of the climate movement in 2000.

Also, re:adversariality, Chinese industrial output is so much dirtier than that of the West that the optimal target would probably be to have never implemented most climate restrictions, since climate change is a global phenomenon. Would reversing them help now? Maybe, idk, if it helps massively with reshoring. If not, the loss of credibility may be severe.

Overall, great post!

Let’s talk about SMR nukes a bit. Not just safe and carbon free but a far better answer to our energy needs than wind and solar.