Just your average budget cut

Recently the state of Connecticut proposed a $38 million cut to the state’s rail transit operator, CTRail. As one might assume, less money for an unprofitable transit service means service cuts. Nobody particularly likes service cuts, and so as soon as this was announced the op-eds were out in force railing against the cuts. The state’s justification for said cuts is that the ridership is simply not there, and so the state is right-sizing the agency’s budget to the ridership. The MTA says that the new budget will reduce the number of weekly trains from 309 to 260, which amounts to 86% of the current service level.

Service Pattern Planning

The New Haven Line, like most commuter rail lines in the US, is no stranger to reduced service. The pandemic necessitated a drastic cut of service levels, which fully eliminated additional peak trains and reduced late-night and early-morning service. From this low base of trains in 2020, service has incrementally been restored. The most recent service restoration was last summer, returning to full prepandemic service despite only 45% of ridership returning. The most recent trains added were mostly rush-hour zone expresses, and some new super-express trains to connect to newly-restored Waterbury Branch and Hartford Line trains. The increase before that was also mostly zone express trains.

Before those express trains were reintroduced, the MTA ran a schedule which fully filled out the timetable with half-hourly clockface locals to Stamford, and then half hourly trains running express to Stamford and then local to New Haven. This kind of service pattern is super cheap to operate: it uses the same number of trains and crews, all day long, so there is almost zero wasted crew time. Furthermore, the trains are timed to stay out of each other’s way, so delays are minimal. Contrast this to the zoned express trains: Because they make specific local stops, they have to stay on the local track and chew up an enormous amount of capacity at the stations they don’t stop at. They don’t run all day, but since crews have to work all day they are much less efficient. Plus, since they can’t all sit in Grand Central, they have to be shuffled into and out of Grand Central during rush hour, and running empty trains is expensive.

As an added benefit to the off-peak service patterns, these service patterns make it much easier to make an intermediate trip, going from town to town instead of all the way to grand central. As a result: intermediate and weekend ridership has almost fully recovered, at about 95% and 80% of prepandemic ridership. Meanwhile, weekday trips have lagged behind, especially on Mondays and Fridays (Monday ridership is ~65% of prepandemic, while Wednesday ridership is nearly 75%).

New Initiatives

While all this has been going on, the government’s rail initiatives haven’t exactly stood still. While the pandemic raged on, several rail initiatives have been completed. The first is a series of upgrades on the Waterbury branch. Service has been increased 47%, up to every 90 minutes in both directions thanks to new passing tracks (service was at one point once every 3 hours, which is abysmal even considering the low ridership). Meanwhile, the Hartford line has had the strongest recovery of any railroad in CT. Incredibly, it hit 80% of prepandemic ridership while partly relying on bus substitution. Even Amtrak, with its profitability mandate, has contributed to running more trains on the line.

So, to better connect both lines to Grand Central while also achieving the Governor’s plan to speed up trains, the MTA has introduced new “super-express” trains on the New Haven line, which have only 6 stops: Grand Central, Harlem, Stamford, Bridgeport, and the two new haven stops. In other words, it skips every single minor station. While this does achieve the governor’s stated promise of shrinking end-to-end trip times, almost no regular commuters will see a speedup, so this does feel a bit like an opt-out. At any rate, these trains are another expensive and burdensome initiative that isn’t doing ridership many favors. Even worse, they cannot be cut despite being obvious candidates because of their political importance.

Shore Line East

While all of this has been going on, one other state rail initiative has been struggling. Shore Line East operates (as the name suggests) eastwards out of New Haven, winding through seven stations in relatively minor towns before winding up in New London. For those of you unfamiliar with Connecticut geography, this is the middle of nowhere. If Ohio is a flyover state, New London is a ride-through town - its existence is only notable as a point between New York and Boston. An interurban rail route to such an isolated town can only really exist because trains already pass through there anyways - Shore Line East is essentially a local service to Amtrak’s Northeast Regional.

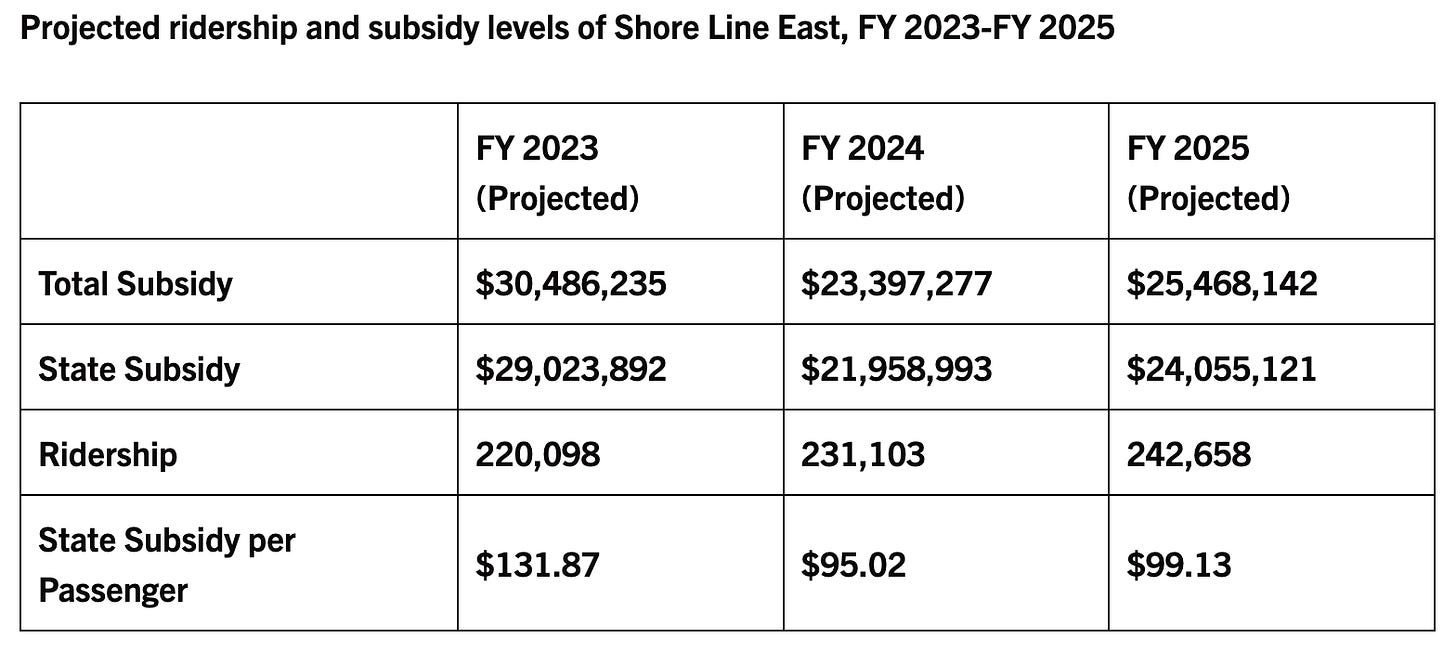

Shore Line East was originally a temporary service to ease congestion due to a partial closure of I95 in 1989, and was retained as a state initiative to reduce congestion. While setting up commuter rail service on an existing rail line was very easy, the tiny population of its towns meant getting people to ride it has been very difficult. Already-low ridership got clobbered by the pandemic and never recovered. The trains have become so empty that the effective per-rider subsidy this year is expected to be an eye-watering $131 per passenger (one way!). While writing this article, I did some anecdotal research, and an uber the full length of the rail line seems to be about $75.

So, Which Trains to Cut?

Let’s start with the obvious answer - Shore Line East is slated for cuts, and rightly so. It’s sad to see service shrunk to an almost-useless amount, but it never made sense anyways. High per-rider subsidies are acceptable on the Hartford Line, where ridership is actually increasing, On Shore Line East, however, with no signs of improvement, this level of money loss is not reasonable.

Moving onto Metro North (which, as most of the trains was always going to bear most of the cuts), the answer to this question still seems obvious. The pandemic has clobbered weekday ridership, especially on Mondays and Fridays, while weekend and intermediate travel have mostly or entirely recovered. The off-peak timetable is also much more efficient than the zone express trains, delivering a lower cost per revenue trip, and the ridership for the expensive express trains isn’t materializing anyways. Plus, the MTA has revealed which trains are most important when deciding which ones to reintroduce after the pandemic. It’s clear that the zoned express trains are the most expensive and the least important - so cut the zone express trains. Last in, first out.

The MTA has decided otherwise. Seemingly in a play to maximize voter pain, the MTA has threatened lower all-day frequencies, saying that it would be “very difficult” to prevent peak hour service cuts, implying that just many other trains would get cut first. While I understand that the MTA plays lots of power games, and this might be the most effective way to argue against a cut, it seems just a little outrageous that the MTA is deliberately removing more useful trains to make a point to the state of Connecticut. It is perhaps the most pure example I’ve seen of an agency making its own policy in spite of legislative intent.

(Surprisingly), An Easy Way Out

The fundamental problem at the core of all of this is that a railroad has a high fixed cost to maintain, even if zero trains are running. The only real costs which are affected by how many trains are operated is labor (electricity as well, but this cost is trivial compared to labor). In other words, almost all of the $38 million in savings is going to be the result of employing fewer people and thus running less trains. However, if the trains could magically complete their runtimes in 86% of their current schedule, then they would consume only 86% of the current cost of operation per train. The budget cuts could then be made, and instead of reducing trains, we would get the same number of trains, except with faster service. This obviously sounds like a pipe dream - there shouldn’t be a reasonable way the trains could just be 15% faster

Except there is. The MTA currently “pads” their schedules way more than international standards, especially on the new haven line. Take for example the first train of the day - the 5:28 local from Grand Central to Stamford, arriving 70 minutes later at 6:38. In theory, this train represents the best-case scenario - with no other trains running, this train should represent the maximum possible speed for a local. Indeed, it’s 7 minutes (10%) faster than the train leaving Grand Central at noon, and the same is typical for trains leaving at 5:30 (76 minutes) and 6:50 (74 minutes).

However, pay closer attention to the timetable and you’ll notice that our 5:30am train takes a whopping 10 minutes to go between the penultimate stop (Old Greenwich) and the last stop (Stamford). This is despite the same pair of stations only taking 3 minutes in the other direction. This is obvious statistical manipulation by the MTA - the train can, by going between these two stations at a regular speed, manage to make up 7 minutes, and therefore be marked as on time even if it runs the whole route late. Thus, our unpadded time isn’t 70 minutes but 63 minutes. 63 minutes is a hilariously small 80% of the time required of our rush hour train, and 84% of the 75 minutes that the midday trains take.

In other words, the MTA’s statistical inflation means that the trains are much slower, and much more expensive, than they need to be. If the MTA simply ran the trains in a way that didn’t include random 10 minute delays, the required budget cuts could be made without affecting the number of trains operated.

The MTA will not run the trains more efficiently - they will make the most damaging possible cuts to try and force the state to cave. Maybe they will, or maybe they decide they’re done with the agency’s shenanigans. Either way, the core of the conflict lies not in underfunding, or malice on the part of Ned Lamont, but on sheer institutional rot in the MTA. And in case you’re not mad already, nobody has come up with a good way to fix it.

Have a nice wait for your train.

This is actually quite nicely written.