Potential Problems Pertaining to Public-Private Partnerships (P6)

I guess I need to keep saying this, but republicans should think about writing their transportation platform *before* writing it.

I. Ascertaining Agenda Alterations (A3)

Republicans don’t think about transportation, and when they do it’s usually annoyance that the government is involved at all. That is in keeping with their small-government roots, but it borders on the extreme. For example, the republican platform for 2025 discusses transit for only one sentence:

“We propose to phase out the federal transit program and reform provisions of the National Environmental Policy Act which can delay and drive up costs for transportation projects… Recognizing that, over time, additional revenue will be need to expand the carrying capacity of roads and bridges, we will remove legal roadblocks to public-private partneship agreements that can save taxpayers money and bring outside investment to meet a community’s needs.”

I’m not *entirely* sure what “federal transit program” means, but I presume it means “Federal Transit Capital Investment Grant Program”. Noting the need to outline some kind of replacement, they point to public-private partnerships.

Project 2025 agrees with that sentiment, but expands a little more. They feature a whole section on public-private partnerships. The first paragraph is this:

“Much infrastructure could be funded through public–private partnerships (P3s), a procurement method that uses private financing to construct infrastructure. In exchange for providing the financing, the private partner typically retains the right to operate the asset under requirements specified by the government in a contract called a concession agreement. In addition, the private partner is given the right either to collect fees from the users of the asset or to receive a periodic payment from the government conditioned on the asset’s availability: If a highway is not open to traffic when it should be, for example, the government’s payment to the private concessionaire is reduced.”

They then go on to discuss how, having used these new P3 agreements, they then go on to talk about the grant programs they will end, including the Capital Investment Grant (CIG). That’s the program that the federal government uses to fund most mass transit projects in the US. Per them:

“Because Americans have demonstrated a strong preference for alternative means of transportation, rather than throwing good money after bad by continuing federal subsidies for transit expansion, there should be a focus on reducing costs that make transit uneconomical. The Trump Administration urged Congress to eliminate the CIG program, but the program has strong support on Capitol Hill. At a minimum, a new conservative Administration should ensure that each CIG project meets sound economic standards and a rigorous cost-benefit analysis.”

What you can sort of cobble together from these statements is that Republicans want the federal government out of funding transit. As a replacement for those funds, they want cities to use P3 programs to fund their transit programs.

II. Making Mechanisms Move (M3)

One potential reading of this move is that they simply do not want to extend transit lines at all. It would be fine if they just came out and said that, but I’m going to be charitable and assume this proposal is in good faith. It is indeed true that there are mechanisms to involve private money in mass transit, and infrastructure projects more generally. The only problem is that they are pretty roundly hated, and this takes some explaining.

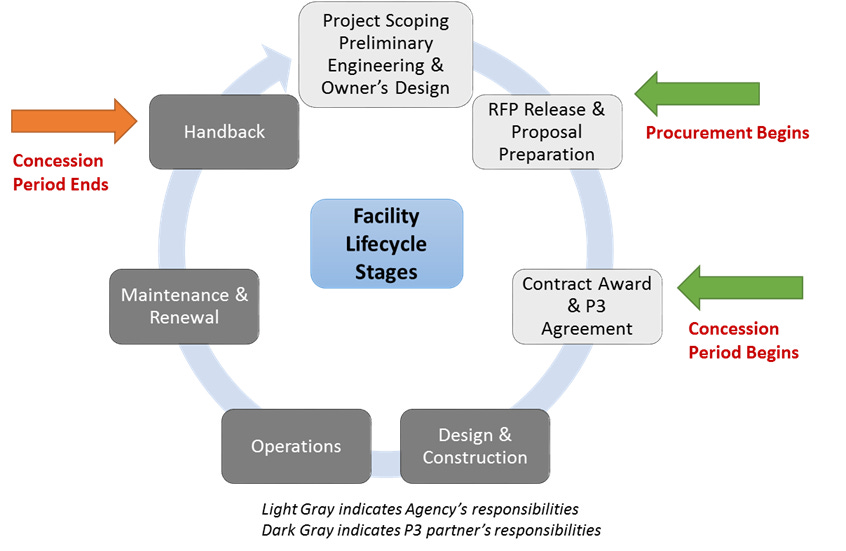

The basic principle behind P3s is that governments are ill-equipped to handle part or all of the construction process. The government, therefore, contracts out part or all of an infrastructure to the private sector. There are four parts to an infrastructure project: Design, Build, Operation, and Maintenance. The delegation of these tasks falls along a continuum, and the more they contract out (especially the last two) the more likely a project is to be considered a P3.

Most governments contract out at least part of every project. For example, the government usually contracts architecture firms to design non-road transportation infrastructure. They also typically hire contractors to physically do the building - construction site employees aren’t usually direct government hires. The first advancement in the field of government contracting was the “Design-Build” contract.

These contracts work exactly how you think they do. The government would hire the same company to design and build a project, encouraging the contractor to come up with cheap, efficient designs. Policy reformers carried this forwards - if one company had to do all four functions, they would optimize for the most efficient overall project, including operations and maintenance.

Thus, the DBOM contract was born. (Or DBFOM, if you include finance). Since projects are usually not immediately profitable, the government in these contracts pays the contractor upfront, or during delivery of service (as an extra subsidy), hence where the partnership comes from.

However, DBOM contracts are only the most aggressive form of public-private partnership. In most road deals, the state operates tolled lanes themselves, and agrees to pay the private part of the partnership some of the toll revenues in exchange for some amount of cash upfront, which helps fund the project. In some cases, the state will even guarantee revenue in the case of underperformance, making the P3 effectively just a public bond.

III. Featuring Former Follies (F3)

Before beginning this section, it’s worth noting that in cases which are more privately led (DBFOM vs state-led revenue share), the end result of a P3 is essentially a privatized road. In fact, the entire structure of these projects is identical to one where the state builds and then privatizes the road.

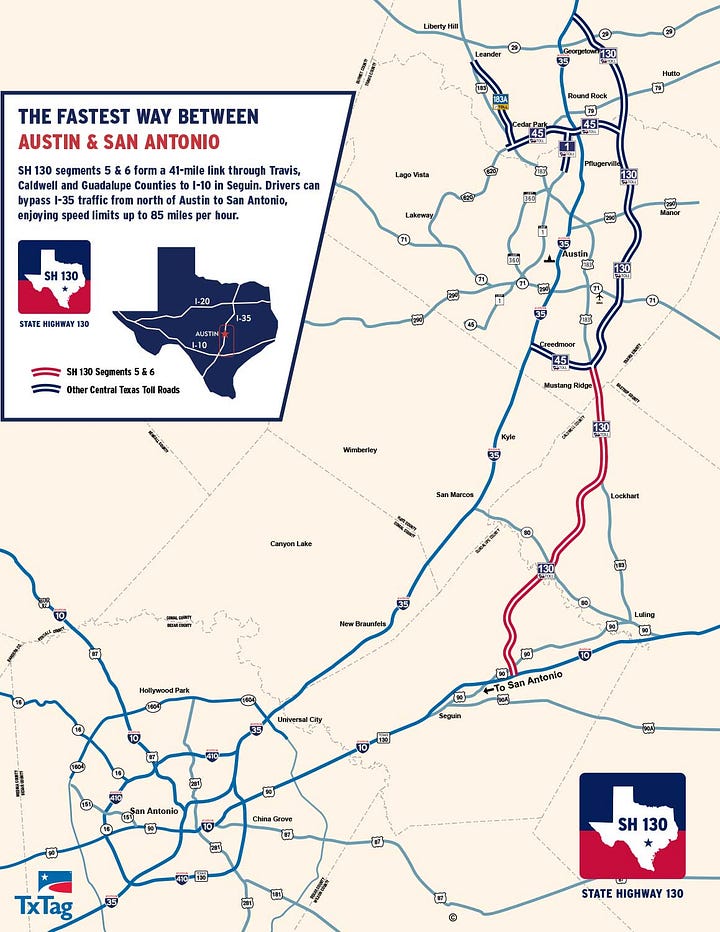

The first and most notable case of a P3 failure is Texas State Highway 130. The route was planned after the US joined NATO, and truck traffic through Texas increased. To cope with the new traffic, the Texas DOT planned a highway around San Antonio, bypassing Austin, and then merging back onto I-35 after it. TexDOT didn’t actually have the money to build the road, however, so they contracted with private investors to build the road, in six separate segments.

The problem arose in segments five and six, which connected the San Antonio section of TX-130 to the Austin section. The road served basically the same purpose as I-35, 20 miles away. It was a rural highway connecting the two cities. The only problem was that I-35 was free, and TX-130 was not. The state even managed to approve a speed limit increase to 85mph - the highest in the country - but traffic counts did not meet expectations.

As is supposed to happen in private infrastructure, there was a bankruptcy, ownership was transferred, and revenues managed to stay above operating costs. But I-35 continues to be congested, so now Texas is spending $4.5 billion to widen I-35 (the wider highway will still not have toll lanes). That’s not even bad policy, but I can’t imagine the current TX 130 owners are happy about this.

A similar story can be told for the interstate 95 express lanes in Northern Virginia. Tolls are levied on three reversible lanes along 41 miles of Interstate 95, bringing commuters across the Potomac, either into downtown DC or via the beltway. The same route is also served by the Virginia Railway Express, which runs a commuter service from Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania to L’Enfant and Union Station.

The only problem is that VRE is not required to be profitable. They are theoretically required to maintain a 50% farebox recovery ratio. Realities of the COVID Pandemic have made that difficult to achieve in practice, but the agency itself is not helping. Track capacity is expected to open up after upgrades to the (borderline profitable) DC-Richmond line opens. VRE plans to use this capacity to run dramatically more trains, driving farebox recovery ratios down to 16% by 2050.

The problem in both cases is that public officials seem to think that P3s are simply a way to treat the private sector as an ATM to pay for their infrastructure ambitions. The problem is that those investors have interests other than being an ATM for voters. Especially if republicans intend to use P3s as a primary funding mechanism, this perception cannot continue. In particular, privatization means that officials cannot promise to “get cars off the road” to reduce traffic - cars on the road (and more importantly, congestion) is how investors make money!

Failure to respect private investors interests in P3s is extremely easy electorally - in fact, respecting them is an easy way to construct a losing platform. However, the higher the risk of betrayal by private officials, the higher the return investors will expect for these projects. That would increase highway tolls paid by most Americans, especially if P3s become a dominant funding mechanism. If Republicans are serious about that, they must also take seriously the protections they plan to offer the investors on the other side of the table.

Project 2025 seems to acknowledge that using P3s does in fact mean paying for roads:

“Some mistakenly think that using a P3 would allow a road or bridge to be delivered without increases in tolls or taxes. It is important to remember that all funding for governmental infrastructure comes from either taxes or user fees. P3 financing can be used to make those funding sources more efficient, but it cannot replace the need for taxes or user fees to provide the funding for the project.” (p624)

But there is no discussion of protections from investors. There’s also no discussion of transit, which is much worse.

IV. Mass Mobility Maladies (M3)

All of this gets a lot worse when the discussion moves from highways to trains. Unlike with cars, transit payments cannot simply be collected on all users going through one point. They are instead paid when a user gets on the train, or occasionally they are determined when a user gets on or off. In larger networks, passengers may take multiple routes to their destination. Privatization is difficult, because if public and private trains are mixed, it becomes impossible to know which customers used which trains.

That can be designed around, although in systems like New York, where riders only pay when entering, that becomes difficult. Accurate public-private-partnerships would require a redesign of fare gates, which in a system of over 400 stations would take a while. Things become more difficult when the government attempts to use a P3 to extend an existing, government owned line.

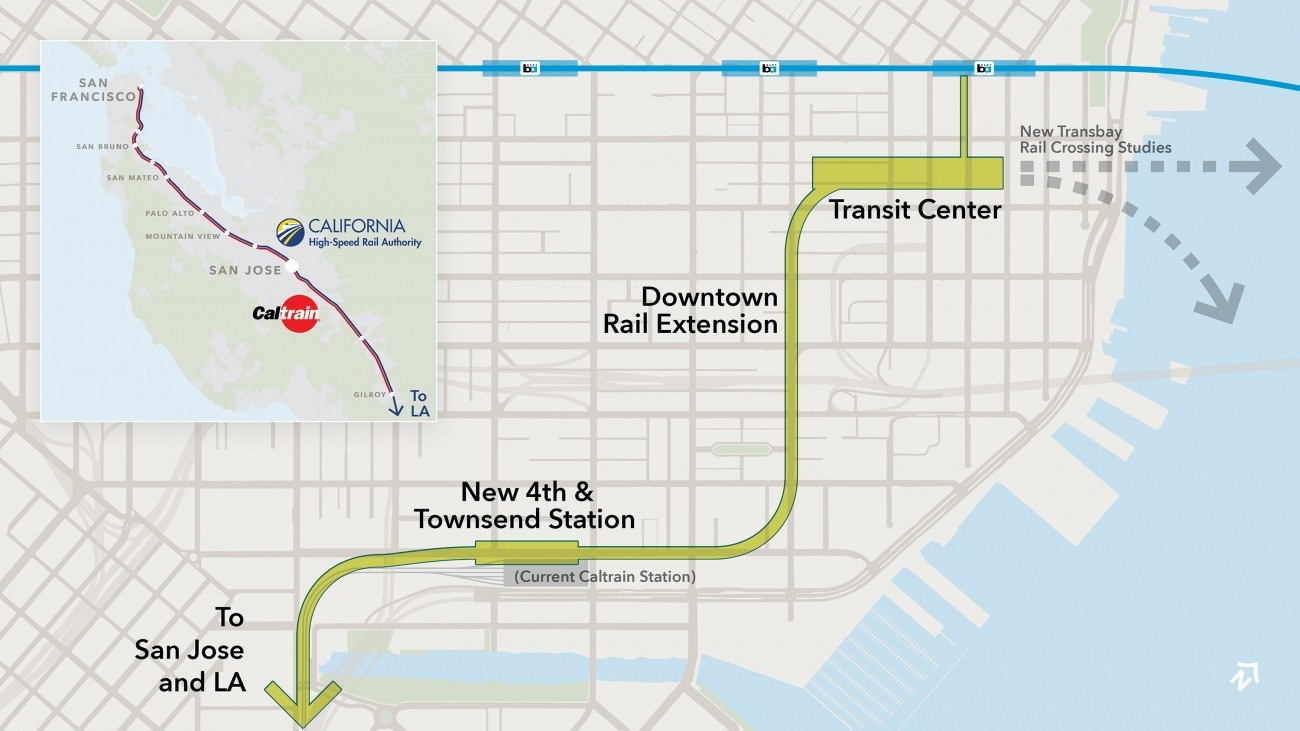

Let’s take the case of the two-mile Caltrain extension from 4th and King to the Transbay Transit Center. It was designed to collect the Bay Area’s suburban buses, and put them under the same roof as Caltrain, and eventually California High-Speed Rail. It’s surrounded by skyscrapers, in a much better location than 4th and King, two miles and half an hour by streetcar to downtown. Since Caltrain is a commuter railroad designed to bring office workers to downtown, most ridership would shift from 4th and King to the Transbay Transit Center.

The project will cost between $6 billion and $8 billion. Let’s say that Caltrain decides to go with a P3 to fund the extension, and a private company ends up owning the tunnel. How should the company be compensated? One idea would be to have the company charge Caltrain per-train fees. However, Caltrain doesn’t make a profit either - it’s dependent on government funding to run trains. If a later political conflict were to reduce Caltrain’s funding, and thus the number of trains to downtown, how should investors be compensated?

To fix the train volume uncertainty, the government could instead privatize Caltrain, and then have the reverse arrangement - the government charging the investors to operate trains on their tracks. Again, a problem arises - how much should the fees be? How much should the private company be allowed to make? What should fares be?

V. Committing to Consistency (C2)

Since time is a flat circle, this is actually not all that new. In fact, the New York City subway system was built like this, back when rail transportation was a profitable industry. Private companies couldn’t just build subways under public roads, and disrupt traffic for years without government approval. So, the city made a deal with the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT), which was in 1900 really just a consortium of investors.

First, the IRT would design the subway infrastructure they wanted to own. They would then present the government with those plans, which would hire the IRT to build them. When the system was done, the city would own it in name. In practice, the city would lease the project back to the IRT for 999 years. Then, the IRT would operate the subway in perpetuity.

The fatal flaw in this design was that the government still actually owned the tunnels. Because it was 1900, the leasing agreement stipulated that the IRT would run trains at a five-cent fare, forever. In 1900, that was reasonable, because the economy was on the gold standard and money didn’t lose its value over time. Then it did, but the city refused to raise the fare. The IRT took the city to court and lost, eventually declaring bankruptcy in 1940.

In almost every case, P3s leave price discretion to the government. In Virgina, the government sets maximum rates on toll roads. Toll limits are set by allowing toll operators “no more than a reasonable rate of return”. Tolls on the Chicago Skyway are capped at 2% increases per year, inflation, or GDP growth. New York capped IRT fares at five cents.

Toll increases and expansions are extremely unpopular. So much so that politicians frequently feel the need to ban them. Even in Republican Texas, the proposed solution to TX-130 is to buy out the operators and remove the toll. This in fact negates one of the key advantages of P3s: since investors are not controlled by voters, they can raise user fees and generate more revenue than governments can.

I admit I am sympathetic to the republican position on P3s. I have long been in favor of higher user fees for transit and highways. However, it’s very clear that this is an opinion that comes from ignorance. P3s are unpopular among infrastructure planners for a good reason! Tolls are unpopular among voters, and toll limits are unpopular among investors.

A serious proposal to expand P3s would address those concerns. It would specify that cities and transportation authorities can’t limit fees, and leave pricing power up to investors. It would involve some kind of noncompete regulations, where the government can’t parallel an unprofitable service parallel to a privatized one that investors paid the government for.

I’m writing this because the stakes here are pretty serious. Everyone has to use infrastructure, which has so far been thought about and advanced by only one party. I would like to see inter party competition on issues like infrastructure finance, mass transit operating patterns, reasonable levels of service, and so on.

If investors cannot make a return because of price caps, or will be undercut by other government projects, they simply will not invest in American infrastructure. That’s definitely not an outcome that anyone wants. But avoiding it requires thought, and that thought seems to be missing from an otherwise thorough platform.

PS: P3 is a stupid acronym. It’s awkward to pronounce (P three? P cubed?) and saves no time. I don’t see any problems with PPP. Can we use that?